In the age of smartphones, instant messaging, and satellite communication, it’s easy to forget that a series of dots and dashes once revolutionized how the world communicated. Yet Morse code, born out of 19th-century ingenuity, remains a remarkable milestone in the history of communication. More than just a sequence of tones or blips, Morse code opened the floodgates for global interaction, ushering in the telegraph age and laying the foundation for modern digital communication. This is the story of Morse code—how it came to be, how it changed the world, and why it still echoes in niche corners of our technological society.

The Spark of Innovation: Samuel Morse and the Telegraph

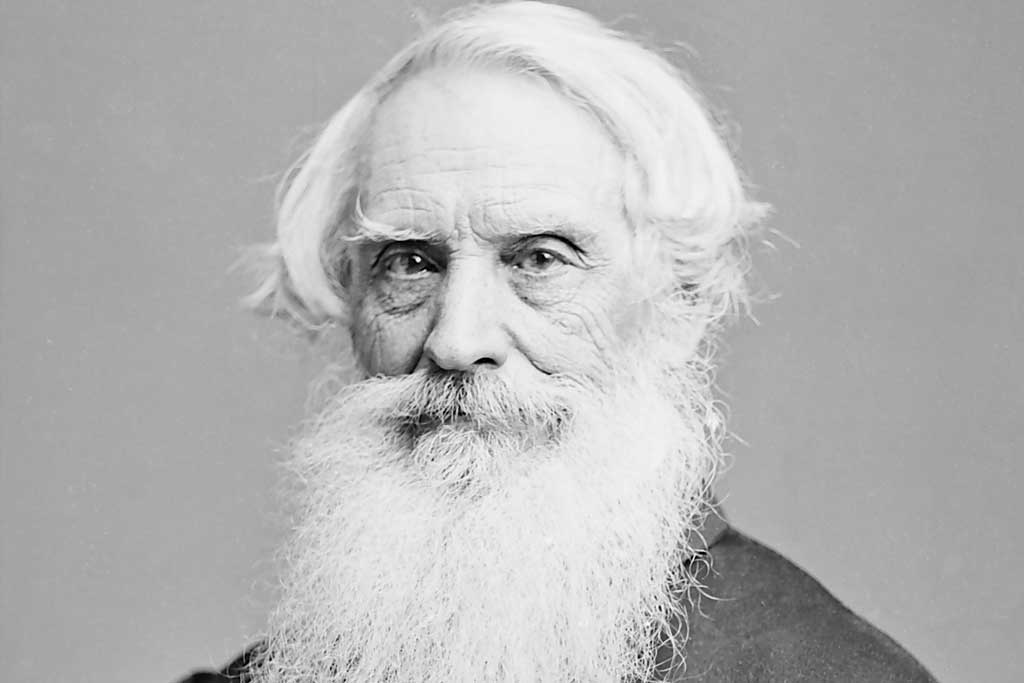

The story of Morse code is inseparable from the invention of the electrical telegraph system. In the early 1830s, Samuel Finley Breese Morse, an American artist and inventor, was struck by an idea while aboard a ship returning from Europe. After learning about recent developments in electromagnetism, Morse envisioned a way to transmit messages using electric current across wires.

Morse wasn’t the first to think about sending messages via electricity—European inventors like Charles Wheatstone had been experimenting with similar ideas—but his vision was practical and scalable. He collaborated with Alfred Vail, a mechanical engineer, and Leonard Gale, a professor at New York University, who both helped develop the hardware and the encoding system that would eventually become Morse code.

By 1837, Morse had constructed the first working telegraph prototype. It used pulses of electricity to move an electromagnet, which in turn marked moving paper tape with dots and dashes. These markings represented letters and numbers—a revolutionary idea at a time when long-distance communication was limited to handwritten letters carried by horseback or ship.

Inventing the Code: Simplicity in Symbols

Morse and Vail’s next challenge was developing a system to convert letters of the alphabet into signals. This wasn’t simply an alphabet with equal-length symbols. Instead, the code was optimized for speed and efficiency. By analyzing how frequently each letter appeared in American English, Vail assigned shorter signals (dots and dashes) to more common letters. For example, the letter “E”—the most common letter in the English language—is represented by a single dot. The letter “T” is a single dash. Less common letters like “Q” or “Z” received longer combinations.

This variable-length coding made Morse code fast and effective, particularly for trained operators. Unlike modern binary systems, Morse code was tailored to human senses—audio beeps, visual flashes, or mechanical clicks—making it versatile and easy to adapt to different technologies and environments.

The First Transmission: “What Hath God Wrought”

On May 24, 1844, Morse sent the first official long-distance telegraph message from the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. to the B&O Railroad Depot in Baltimore, Maryland. The message—“What hath God wrought?”—was a biblical quote from Numbers 23:23 and was suggested by Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of a friend in Congress.

This moment marked the dawn of a new era. The successful demonstration captivated the public and politicians alike, leading to rapid investment in telegraph wires across the country and, eventually, the world. The first message had proven that information could travel faster than any man on horseback.

Standardization: American vs. International Morse Code

As telegraphy spread across nations and continents, so did variations in the code. The original system developed by Morse and Vail, known as American Morse code, was predominantly used in the United States and featured more complex spacing and additional characters.

In contrast, the International Morse code—developed in the 1850s and adopted in 1865—simplified the system and standardized it for global use. It eliminated many of the quirks found in the American version and introduced codes for special characters and punctuation marks.

Though similar, the two versions were not directly interchangeable, which led to a transitional period where operators had to be proficient in both systems, depending on whom they were communicating with. This standardization played a significant role in helping messages span long distances efficiently, including across the Atlantic Ocean via undersea cables.

The Golden Age of Telegraphy

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, telegraph networks expanded dramatically. Undersea cables connected continents, and Morse code became the lingua franca of international diplomacy, news transmission, and commerce.

Telegraphy revolutionized industries. Financial markets thrived on real-time updates. Newspapers could report events from distant lands almost instantly. Railroads used telegraphs to manage logistics and prevent collisions. For the first time, human communication was no longer bound by geography or the speed of physical travel.

Telegraph operators became the unsung heroes of this era, decoding and sending messages with lightning speed. Mastery of Morse code was a valued skill, and schools opened to train new generations of operators. Companies like Western Union laid thousands of miles of telegraph wire, fueling the rapid expansion of this new information network.

From Wires to Waves: Morse Code Goes Wireless

The next great leap came at the turn of the 20th century with the development of wireless telegraphy. Guglielmo Marconi and others pioneered methods to send Morse code over radio waves, eliminating the need for physical wires and extending communication to ships at sea.

This proved invaluable. Maritime communication entered a new era, with ships able to contact each other or land stations from hundreds of miles away. This had life-saving implications, particularly in emergencies. One of the most famous uses of Morse code occurred during the sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912. Wireless operators aboard the doomed ship sent distress signals (“CQD” and the newer “SOS”) that were picked up by nearby vessels. Although over 1,500 lives were lost, the use of Morse code was credited with saving hundreds of others.

Military Applications and World Wars

During World War I and World War II, Morse code was used extensively by all major powers for tactical communication, especially in the field and at sea. Radio operators transmitted battlefield updates, espionage communications, and coded commands across the globe.

To secure these messages, militaries began encrypting Morse transmissions using codebooks and ciphers. In some cases, entire teams of codebreakers were assembled to intercept and decode enemy messages—most famously at Bletchley Park in England, where the Allies decrypted the German Enigma codes.

Radio silence, brevity codes, and call signs became standard military procedures, and Morse operators were considered critical to mission success. The beeping signals became the soundtrack of war, from the trenches of Europe to the jungles of Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War.

Decline in the Digital Age

By the mid-20th century, new technologies began to overtake Morse code. Voice communication over radio became more reliable. The rise of teletypewriters, fax machines, and eventually digital data transmission made Morse code increasingly obsolete for most commercial and military applications.

In 1999, the International Maritime Organization officially removed Morse code as a requirement for maritime distress communication, replacing it with the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS), a satellite- and digital-based alert system.

By the early 2000s, Morse code training was no longer mandatory for amateur (ham) radio licenses in many countries, signaling its sunset as a mainstream communication tool.

A Signal That Won’t Die: Morse Code Today

Despite its obsolescence in official channels, Morse code has never truly disappeared. It continues to have a dedicated following in the amateur radio community, where hobbyists send Morse over high-frequency bands to communicate across continents with minimal equipment and power.

It also finds a place in emergency communication, where simple, low-tech signaling can still outperform complex systems during natural disasters or technical failures. Pilots and air traffic controllers still use Morse identifiers for navigation beacons like VORs and NDBs.

Outside of radio, Morse code has even crept into modern culture and technology. People with speech impairments have used Morse with adaptive devices. Apple introduced Morse input on iOS for accessibility users. It’s even shown up in movies like Independence Day and Parasite, where characters send secret messages in Morse.

In the broader cultural landscape, Morse code maintains a mystique. The sound of the code—short bursts and long tones—is instantly recognizable. It symbolizes secrecy, urgency, and resilience. Even the SOS distress call (“…—…”) has become universal shorthand for “help.”

Why Morse Code Still Matters

Morse code’s relevance today goes beyond nostalgia. It serves as a powerful reminder of how innovation can transform the world. It’s a study in efficient design, offering lessons for coders, engineers, and communicators alike.

Its longevity also highlights something unique: simplicity endures. In a world obsessed with faster, sleeker, more complex systems, Morse code remains a humble testament to human creativity. It is proof that even a system made of dots and dashes can bridge oceans, save lives, and shape history.

Fun Facts About Morse Code

- The longest Morse message ever sent was by a ham radio operator in California in 2004. It contained over 100,000 characters.

- The U.S. Navy transmitted its final Morse code message in 1999 with the phrase: “Going out of style.”

- Morse code is still used in aviation to identify navigation aids—each beacon sends its name in Morse every few seconds.

- Some smartphone flashlight apps allow users to send SOS messages using the camera flash.

Related: