Plato, the man, wrote about politics, reason, ethics, the nature of the soul, and much more. His work is so influential that most of it is believed to have survived over the past 2,400 years.

PLATO, the computer system, has been around for about 50 of those 2,400 years. That may not be long in human terms, yet it’s a lifetime in tech — a testament to just how much influence this PLATO has had in its own way.

PLATO, short for Programmed Logic for Automated Teaching Operations, came about at the University of Illinois in the early 1960s. Its intended use, teaching, was reflected in its name. But it did so much more than that: laying the foundation for email accounts, message media, and many other web technologies we enjoy today.

An exciting time in the computing world

PLATO emerged in the 1960s, an important decade for computing. At the time, computers were big machines that lived in a central lab. While it was a great setup for the researchers who had access, the machines’ utility was limited for just about everyone else.

Around the globe, academic projects began cropping up to address this issue, with central computers (mainframes) connected to client devices (terminals).

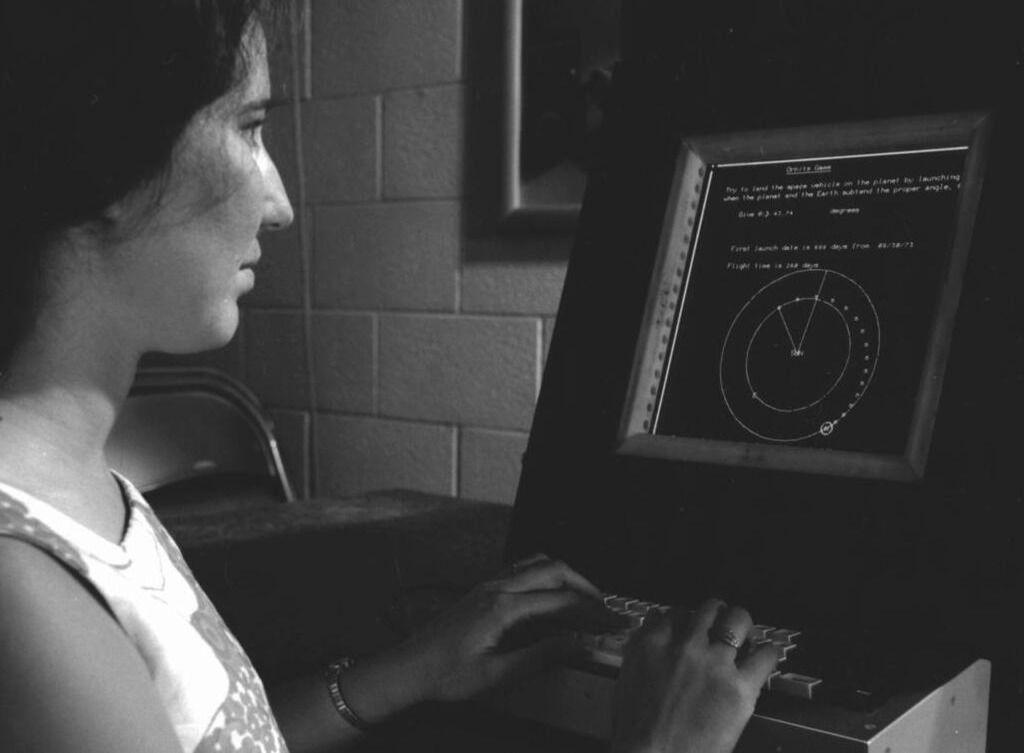

Initially, the aim was computer-assisted teaching. PLATO’s innovation was to make education terminals graphically appealing, researcher Don Bitzer wrote in 1976.

“The terminal included a computer-generated graphic display and superimposed computer-selected slides,” he said.

Expanding PLATO’s user base

The thesis for PLATO was solid, yet with 1960s technology it was only possible to connect a handful of terminals to a mainframe at a time. That changed in 1972, when the PLATO mainframe was upgraded to allow for up to 1,000 simultaneous connections.

This system upgrade unlocked the real potential of PLATO. Over and above computer-augmented teaching, it allowed for the beginnings of a community to form.

Also in 1972, PLATO’s developers added a feature called Notes to alert users of system outages or bugs. Because each note supported up to 63 responses, PLATO could facilitate ongoing conversations — particularly in the Public Notes section of the system, in which users could post about any number of different topics.

“Public notes became the most popular of the three forums, where users discussed anything from books to politics,” the university’s Illinois Distributed Museum says.

Talkomatic and term-talk

Even as PLATO paved the way for forums and digital communities, it has a connection to online chat, as well.

PLATO was home to the world’s first chat app — known as Talkomatic. In 1973, researcher Doug Brown wrote Talkomatic to allow PLATO users to have conversations in real time.

It looked a lot like the AIM conversations that came a few decades later: with a different message box for each conversation arranged horizontally across the screen. But Talkomatic didn’t actually have a Send button. What you typed appeared immediately as a new message on the recipient’s terminal.

Talkomatic offered both group chats — channels with up to five participants — and a person-to-person option called term-talk. What was notable about the latter is that it predicted windowed operating systems. On term-talk, you could exchange instant messages while keeping other programs running.

PLATO as a commercial product

By 1975, PLATO inventor Bitzer says, there were nearly 150 PLATO sites in North America, responsible for teaching thousands of credit-hours each year.

A company called Control Data Corporation saw the technology’s massive commercial potential. In the mid-Seventies, CDC began licensing PLATO from the University of Illinois and selling it to other academic institutions, government bodies, and businesses.

These disparate PLATO systems were even configured to talk to one another. As long as different sites were linked by communications lines, the Notes functionality of PLATO could be extended between them — enabling “forums” with hundreds or thousands of members.

The growth in PLATO’s user base didn’t just facilitate richer, broader conversations. It also led to the introduction of online games like Spacewar!, Empire, Airfight, and Avatar.

By the mid-1980s, PLATO’s mainframe model was on its way out. Powerful personal computers, available from brands like Apple, IBM, and Tandy (Radio Shack), could do much of what mainframes were capable of.

CDC eventually sold the PLATO brand name and technology to other firms, but it didn’t exit the internet industry completely. The networking technology it developed for PLATO provided the foundation for CompuServe’s online services in the Eighties — and America Online in the Nineties.

PLATO’s heritage

AOL isn’t the only business to have been spun off of PLATO. Lotus Notes, the “groupware” collaboration tool that was popular in the Eighties and Nineties, was launched in 1984 by three engineers — Ray Ozzie, Tim Halvorsen, and Len Kawell — who had met while working at the University of Illinois.

This is just one of the many relationships that came about because of PLATO. Countless friendships, and even marriages, started on the platform: whose unique genius is that it allowed people to find and form digital communities for the first time.

“PLATO was a precursor to today’s online world, with a thriving online community which predated today’s social media by decades,” the Distributed Museum says.

While PLATO came long before illumy, we’re nonetheless inspired by its user base. People always want to connect and communicate in new and better ways that shrink distance: the problem that PLATO solved in the Seventies, and one we’re tackling today.

On illumy, you’ll not only get an email address with a powerful spam filter but will be able to chat in real time with other illumy users. Send and receive a large number of messages in either (or both) formats. Upload avatar images to highlight your personality. Share files with a 500MB size limit. And use the illumy phone app to stay connected on the go — at no additional cost.

In the future, you’ll even be able to get a phone number through illumy. It’s the messages app you didn’t know you needed.